While protesters shut down Board of Regents meetings and teachers’ unions boycott Eastern Michigan University student teachers, the College of Education’s faculty is putting all of its efforts into making sure students never miss out on an educational opportunity.

“Our students are caught in the political crossfire in their last semester of teacher training,” said Barb Stafford, a university supervisor in the College of Education whose job is to find placements for student teachers.

Stafford is just one of an entire team of faculty members in EMU’s College of Education whose day-to-day work has been affected by the university’s affiliation with the Education Achievement Authority of Michigan.

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder created the EAA in June 2011 as a statewide school system for failing schools. However, the authority has yet to move out of the Detroit area. The EAA started taking over failing schools in 2012 and currently oversees 15 schools in Detroit, including nine elementary and middle schools and six high schools.

Since EMU’s Board of Regents signed the interlocal agreement that bore the EAA in 2011, a series of bungled negotiations, money-spending controversies and criticisms of the authority’s efficacy have slowly chipped away at EMU’s status as one of the nation’s most highly-respected teacher-training institutions.

The College of Education is still managing to find student teaching placements for every single student, according to Beth Kubitskey, the associate dean for students and curriculum for the College of Education. It’s just not as easy as it once was to find those placements.

Boycotts

In the fall of 2013, six teachers unions in Washtenaw County Education Association were the first in the area to announce that they would boycott EMU student teachers until the university withdraws from their agreement with the EAA. Since then, unions all over Michigan have announced similar boycotts.

Stafford said she used to be able to place almost all of her student teachers in Livonia schools without any trouble. As of the end of the semester, she had only heard back from two teachers in Livonia who are still willing to take her students. The rest have declined her students on the basis of union boycotts.

“I have worked with Livonia schools for 10 years, and now they’re not taking our students anymore,” she said. “That doesn’t mean they’re not taking student teachers. It just means they’re getting them somewhere else.”

Stafford is most concerned about losing loyal teachers even if the EAA is struck down and the boycotts cease.

“I’m worried the longer we wait, they might not take EMU student teachers anymore,” she said.

Fred Klein acquired both of his teaching degrees from EMU and now serves as the Ann Arbor Education Association vice president. The AAEA was the last union in the area to join the boycott in the fall of 2014.

“It was a very difficult decision,” he said. “We entered reluctantly with the hope that that pressure would have the effect that we wanted – to force EMU to end the interlocal agreement with the EAA.”

Kubitskey said the faculty in the College of Education is working hard to act as buffer between the students and the backlashing teachers’ unions.

“They’re harming the wrong people,” she said. “Luckily, we have still been able to accommodate everyone with placements and jobs, but it has impacted the work of the College of Education in terms of collaborations and projects.”

Klein blames EMU’s Board of Regents for not putting an end to it by cutting ties with the EAA.

“We went into it knowing that EMU student teachers are the unwitting victims of this whole thing, but again it was like, what else can we do?” Klein said. “We took that drastic measure and we were hoping that it would be a one year thing and that we would be able to start welcoming EMU student teachers back into our schools, but so far no movement.”

Stafford, a former Huron Valley School District teacher, said she understands and supports the unions’ plight.

“I support the teachers’ decision to not take EMU students,” she said. “These teachers feel personally attacked by the EAA … the EAA is blaming under-performance in schools on the teachers. People need to understand they have these students when they’re hungry, abused and so on.”

Wendy Burke, the EMU’s director of student teaching, said that right now the College of Education and the boycotting teachers’ unions unfortunately have to stand against each other in order to work together against the university’s continued relationship with the EAA.

“Eastern has incredible relationships with school districts in the state of Michigan,” she said. “We are one true family and we’re going through a tough time right now.”

Another year with the EAA

In order for the EAA to exist, the interlocal agreement requires the participation of one public university and one public school district. Home to the lowest-performing schools in the state, Detroit public schools became the obvious choice for the participating public school district, but the story of how EMU came to be the participating public university is still relatively unclear.

Snyder came to EMU’s Board of Regents with the offer to participate in the creation of the EAA in the summer of 2011. The Regents – who are all appointed by Snyder – hastily agreed to take part in the interlocal agreement, failing to inform the College of Education about their plans to uphold this statewide district until the deal was done.

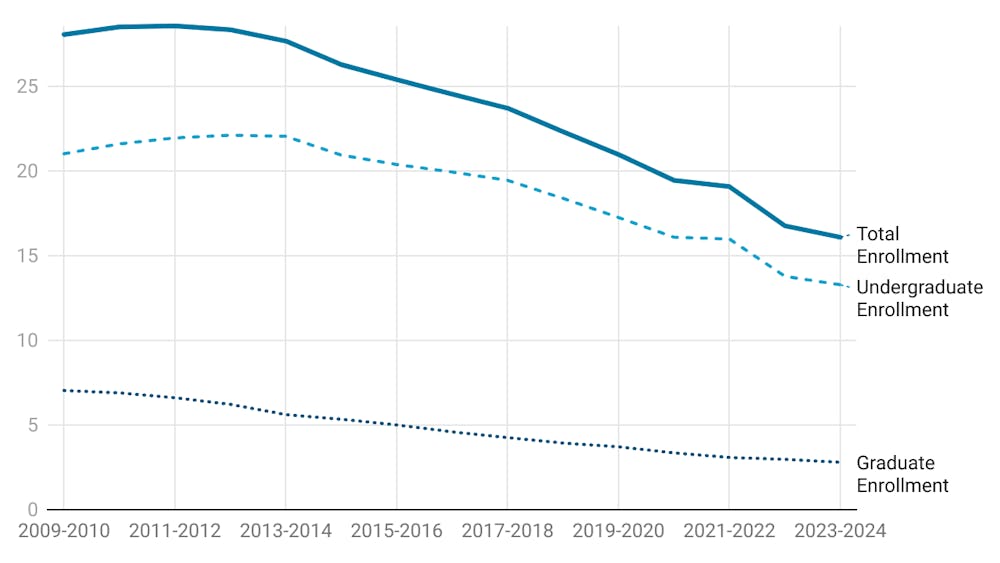

Leaving the College of Education out of the negotiations made for tension between the faculty and the Board before the EAA even stepped foot inside of a school. To add insult to injury, the first few years of the EAA were anything but successful. Test scores continued to drop, teacher retention was abysmal and enrollments were quickly declining.

As the first opportunity for the Regents to pull out of the agreement approached in December 2014, it appeared the Regents were finally reading the writing on the wall.

On the docket at the Board’s regular meeting in December was a resolution to withdraw from the interlocal agreement, which would effectively terminate the existence of the EAA unless Snyder was able to find another public university in the state to take EMU’s place.

The steadily growing group of EAA naysayers and even university president Susan Martin were shocked and disappointed when the Board refused to vote on the resolution until it was amended to push back the withdrawal date by a full year unless meaningful improvement is seen before that time.

“I think this could be something we could be proud of,” said Mike Morris, the new Board of Regents Chairperson, in an interview shortly after the December meeting. “If we don’t see the improvements we want to see, we will vote to withdraw in December.”

Morris, the author of the amendment to the withdrawal resolution, thinks there is a way to make the EAA work and doesn’t want another school to be able to swoop in and become part of that success. He said the problems plaguing the EAA can mostly be attributed to the laissez faire practices of the authority’s previous chancellor, John Covington, and that newly-appointed chancellor Veronica Conforme should be given a chance to turn things around.

Covington resigned from his position in June, stating he was leaving the job to care for his ailing mother. However, his exit came amid a whirl of controversy, including criticism of the decline in enrollment in EAA schools and suspicions surrounding $240,000 in travel, gas and furniture purchases made on two district credit cards issued to Covington.

Morris did not comment on these controversies, but said that the EAA board was not always impressed with Covington’s communication skills.

“Dr. Covington never provided us with adequate follow up,” Morris said. “[Conforme] won’t repeat those kinds of mistakes … she has an inclusive personality.”

In February, Conforme announced a restructuring of the EAA, which she called “the beginning of a new chapter for the EAA,” consisting of four main areas of concentration: leadership, autonomy, accountability and support.

“We are certainly working on some of the things the Regents laid out for us,” Conforme said in an interview. “I think we have to start with the perspective of ‘not everything went well’ – and we know that – and our job is to get things on the right track and start to make improvements.”

Morris and Conforme have indicated interest in collaboration between the College of Education and the EAA now that Covington is out of the picture, but it might be too late for that kind of reparation.

The College of Education won’t be able to return to its former strength until the boycotts stop, and Klein made it clear that the boycotts won’t stop until EMU cuts ties with the EAA. It’s not just about the past failures of the EAA for these boycotting unions – it’s also about the threat the EAA poses to teachers’ unions.

“We’re concerned about these ‘emergency managers’ from the EAA who can come in and essentially tear up union contracts,” Klein said.

He’s worried that without the protection of the union, teachers are losing their jobs and the ones that don’t could experience deteriorated work conditions.

Conforme doesn’t see it that way. She made it clear that she’s unimpressed by the boycotts.

“It’s blocking opportunities for students. Let’s call it what it is,” she said.

Working overtime

The boycotting teachers’ unions aren’t just refusing to take EMU’s student teachers; these unions are putting a stop to all communication and relationships with the university until the Regents withdraw from the interlocal agreement and cut ties with the EAA.

“It has impacted our work, and that’s – I think – the important story to tell,” Kubitskey said. “It’s impacted the kinds of collaborations we can do – those sustained relationships, those kind of things – or we have teachers that we’ve worked with for years who are no longer working with us. It’s made it much harder, but our faculty and administrators and staff are committed toward trying to buffer it from the students.”

Stafford said she’s spending extra weeks – and sometimes months – just finding student teacher placements while she tries to work around the boycotts. She said she has even cold-called districts to strike up new relationships outside of her normal work radius.

“Before, all of my placements were mostly in Livonia and within a 30-minute drive. Now I’m having to go as far as an hour away for some,” she said.

Dealing with the image problem alone is keeping the College of Education faculty working around the clock, and the university’s most respected program is in danger of falling behind.

“A lot of energy is going into this that could be spent doing other things,” Kubitskey said. “What I find frustrating is that we have another year of putting our energy toward dealing with the repercussions of a decision that we didn’t make or have a say in, and that energy is being taken away from really doing some exciting things with our other school districts.”