The hardest part of writing about the innocence of Conrad Black, the Canadian-born member of the House of Lords and former newspaper mogul, is trying to figure out what he is supposed to be guilty of. As a would-be defender of Black, I feel this gap in knowledge would hurt my case if not for the fortunate surprise, It appears, the prosecution has no advantage over me in this regard.

This may be one reason why the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the use of the “honest services” provision used to prosecute Black was overly vague. A lower court subsequently reversed two of his four convictions, leaving only a single count of mail fraud and one count of obstruction. This is all left of the blitzkrieg of 17 charges and talk of hundreds of millions of dollars of fraud charges Black originally faced.

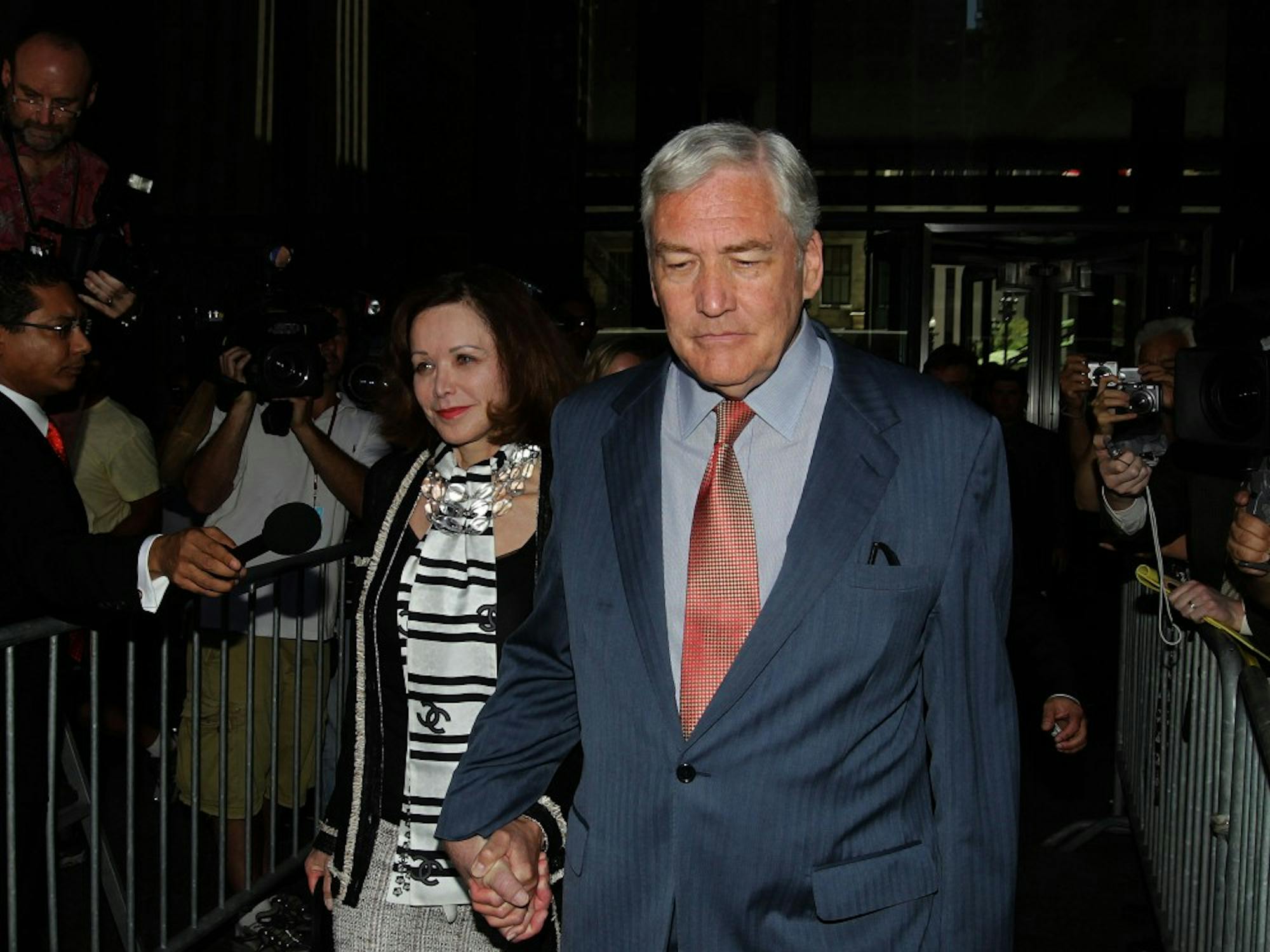

Of course, you only have to bat .011 in the legal system to cost a man two years of his life. With Black now out on bail and awaiting his fate in wake of the recent developments, one can only hope the vindictive mood that culminated with the conviction of Lord Black of Crossharbour has been satisfied.

Leading the mob against Black has been US Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald. An editorial published by the Wall Street Journal pointed out the “railroading” of Black, among other discretions by Fitzgerald and said, “The Fitzgerald method is to abuse the legal process to poison media and public opinion against high-profile, unsympathetic political targets.”

That certainly fits the modus operandi of the man whose high profile pursuits of Libby and Blagojevich have been marred by the same ethical lapses – even greater ones in the case of Libby.

Friends of Black, former President George W. Bush, speech writer David Frum and writer Mark Steyn, have written extensively in defense of him. For that matter, even Christopher Hitchens, whom Black once threatened to buy a newspaper just to fire, seemed to get the gist of the trial. He wrote, “There was, no doubt, an element of class war in the minds of the Chicago jurors as they heard about the astonishing ‘Barbarians at the Gate’ expenditures on parties, jets and all the rest of it.”

Lord Black could have fled the country and lived quite comfortably, but he stayed and faced a jury distracted from justice by class war and an absurd mountain of charges.

When incarcerated, he continued writing, not only contributing columns of politics and book reviews, but writing with social awareness about the justice system and frequently speaking for his fellow inmates and the “tens of millions of undervalued human lives” in the United States. He even served as a prison tutor, taking pride in his work and showing genuine concern for his students.

Black wrote of his new friends and successes as a tutor. “It pains me to verge on platitudes,” he said. “But, life’s rewards do sometimes come in strange ways and unexpected places.”

Black has shown himself to be little of what his enemies have accused. I use this column to suggest Lord Black be given an invitation to be Eastern Michigan’s commencement speaker sometime in the future.