WASHINGTON-The FBI has belatedly awarded $100,000 to a former Minnesota flight school manager whose phone tip eight years ago led to the arrest of al-Qaida conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui, but the bureau gave nothing to a man widely credited as a second tipster.

The reward to Tim Nelson amounts to 2 percent of the $5 million bestowed in January 2008 on an instructor at the Pan American International Flight Academy, where Moussaoui was taking lessons in flying a 747 jumbo jet before he was detained.

The six-figure check wasn’t enough, however, to end a nearly two-year-old controversy over who deserves credit for Moussaoui’s arrest. Underscoring his anger over the size of flight instructor Clarence Prevost’s reward, Nelson filed complaints Tuesday asking two federal inspectors general to investigate whether Prevost cashed in by exaggerating his role as a tipster.

Nelson, a flight engineer who worked as a contract manager at the school until 2004, charged the awards were “manipulated” to dispense checks that met neither “the criteria or spirit” of the State Department’s secretive Rewards for Justice Program.

On Monday, the FBI also awarded $50,000 to Alan McHale, the school’s former No. 2 official, people familiar with the matter said. McHale could not be reached for comment, and there was no immediate explanation as to why he got his reward.

Hugh Sims, another former program manager who’s repeatedly described phoning the bureau hours after Nelson, was passed over without recognition.

E.K. Wilson, a spokesman for the FBI’s Minneapolis office, said “for security and privacy reasons,” the bureau is “not even confirming that any of these guys were nominated for any awards.”

Nelson and his wife, Jodie, accepted his $100,000 reward last week, culminating a lengthy process requiring the signoff of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. During a tense meeting at the FBI’s Minneapolis office, Nelson told McClatchy Newspapers, he vented after years of frustration, criticizing the bureau for fumbling the reward process, and the investigation of Moussaoui.

He said he told FBI agents they missed a chance to nab at least one Sept. 11 hijacker by failing to check Pan Am’s other 13 U.S. flight schools for Middle Eastern students who were loners like Moussaoui.

While he appreciates the money, Nelson said, he told agents that “there were things that were done wrong— and wrong is wrong. … If I had a choice of taking my $100,000 or you getting back your $5 million for taxpayers, I’d rather you get your $5 million back.”

Aimed at encouraging private citizens to turn in suspected terrorists, the rewards program offers cash for “actionable” information. In the Moussaoui case, however, the process degenerated into accusations and finger-pointing.

Nelson asked inspectors general for the Justice Department more money than he did and why Sims got none. He alleged that Prevost, in testimony at Moussaoui’s 2006 sentencing trial, concocted a grandiose account in taking credit for prompting calls to the FBI.

Harry Samit, the highly regarded lead agent in the Moussaoui investigation, said during last week’s meeting Prevost got a big reward because “he testified,” Nelson said. Timothy Gossfeld, an assistant agent in charge of the Minneapolis office, immediately stepped in, insisting the bureau doesn’t pay witnesses, he said.

Despite Prevost’s testimony that pressed superiors to notify the FBI, he arranged for Moussaoui to observe another student’s session in a 747 flight simulator.

Prevost, reportedly in ailing health, couldn’t be reached to comment.

Sims, a highly decorated retired Air Force pilot, said he was “shocked and embarrassed” when the FBI recently told him it had no record of his 2001 phone tip a couple of hours after Nelson’s. But federal law enforcement officials acknowledged years ago both men phoned.

In exasperation, Sims said, he dialed FBI headquarters Monday and reached Dave Rapp, the former Minneapolis agent who took Nelson’s phone tip. He said Rapp remembered him, and his 2001 phone call as well. Rapp didn’t respond to a phone message from McClatchy.

The latest rewards were distributed 22 months after two Minnesota senators, Democrat Amy Klobuchar and Republican Norm Coleman, asked the Bush administration to review whether anyone had been overlooked.

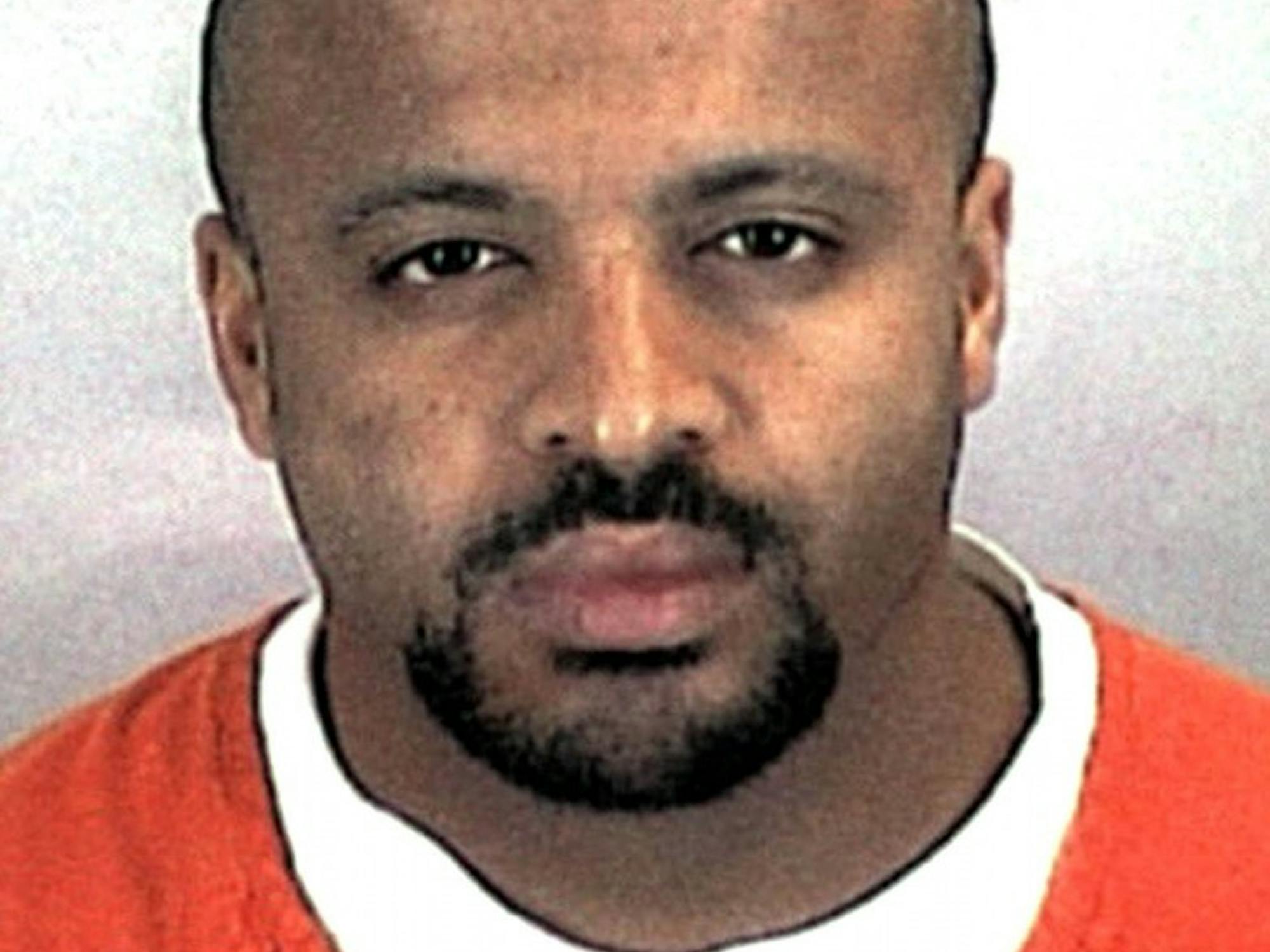

Moussaoui, who was arrested nearly a month before the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, pleaded guilty to terrorism conspiracy charges in April 2005. A year later, a federal court jury spared him the death penalty.

Minneapolis FBI agents have been widely heralded for relentlessly pushing for a court-approved warrant to search Moussaoui’s possessions in the weeks after his arrest, only to be stymied by officials at FBI headquarters.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, a search of Moussaoui’s belongings turned up clues which might have led agents to several hijackers.

Nelson said FBI agents didn’t need a warrant to check Pan Am’s other 13 facilities for Middle Eastern students who, like Moussaoui, had limited flight experience, were unaffiliated with an airline and paid with cash or by credit card.

Nelson recalled a Minneapolis FBI agent seemed shocked at the mention of Pan Am’s Miami headquarters in a phone conversation three days after the Sept. 11 attacks.

The agent responded, “What do you mean? There’s more than one Pan Am?” Nelson recalled.

“I said, ‘There are like 14 in the U.S.’ He kind of sucked air and said, ‘Oh, man, there’s more than one of you!’ It was a surprise or a shock to him.”

Had FBI agents checked the other schools, they might have found another loner, Hani Hanjour, who had taken lessons in flying a Boeing 757 commercial jet at a Pan Am-owned facility in Phoenix. On Sept. 11, Hanjour crashed an American Airlines jet into the Pentagon. The discovery of Hanjour might, in turn, have triggered a nationwide flight school search that identified other hijackers.